Keep it simple

Buying fish can be a slippery business for the ethically conscious shopper. So Rachel Walker asks conservationist Andy Sharpless, CEO of Oceana, to reduce the reams of advice that’s out there to a few simple rules.

Andy Sharpless, CEO of Oceana, the international ocean conservation organisation, admits that it can be tough for consumers who want to do the right thing by seafood. “It’s hard to have species-level information in your head,” he says. “There are just too many species, and what’s available and in season changes too rapidly. Even the names can be complicated – they certainly aren’t always intuitive.”

What a relief. Like many, I’m aware that the oceans are not a limitless resource. They need to be carefully managed, and we as consumers need to make the right choices about what we eat from them. Knowing this much is one thing, but knowing how to act on it is another.

Luckily, I’ve pinned down Andy for a one-on-one chat, to ask his advice. As CEO of the largest international advocacy organisation focused solely on ocean conservation, with offices all over the world, his expertise and knowledge is vast.

I’m worried that his advice will involve me burying my nose in species-identification books and subscribing to industry publications. But I couldn’t have been more wrong: his advice is clear as a bell.

It has to be said, some of his views are controversial – particularly when it comes to fish farming, for example. While many people believe that aquaculture can make an important contribution to feeding a growing global population, generally speaking, Andy isn’t a fan. His point is that all too often wild stocks are depleted in order to cultivate farmed fish, which he believes is an inefficient use of resources. “One of the most common types of farmed fish is salmon,” he says. “And what do the farmers feed their salmon? Fish.”

That said, he admits that there are good and bad farms. “Not all aquaculture is created equal,” he says. “If you’re eating a farmed clam, mussel or oyster, you’re doing something very, very good,” because such shellfish actively filter and clean the water they inhabit. Moreover, lots of farmed species, such as tilapia, catfish and carp are herbivorous and happily gobble up plants. Even so, for the sake of clear advice, his rule (and, we have to say, it’s not ours) is to go for wild over farmed. We’ll go into this debate in more detail in future posts. But for now, with that complexity addressed, here are the rest of his rules:

1. Eat small fish

We’re not talking about young fish here, rather species that never grow big. “Think of it like eating rabbits instead of tigers,” says Andy. Just as it’s much more likely that rabbits will be more abundant than tigers, so it is with fish. In the UK, 80% of the seafood we eat comes from a group known as “the big five”: cod, haddock, tuna, salmon and prawns. With the exception of prawns, the list is made up of top-of-the-food-chain fish. “They require a lot of resources and time to grow to maturity, which is rarely a characteristic of a resilient and sustainable species,” says Andy.

Compare a cod, which can grow up to 150cm and 40kg in weight, to a little mackerel or herring whose minimum landing size is 20cm, or indeed the tiny sprats pictured above, and it’s clear which species is capable of replenishing its stocks more quickly.

2. Eat local

Eating local is generally a good idea for lots of reasons: the food is often fresher and more seasonal, it’s travelled fewer air miles, and you’re pumping money back into local economies too. And when it comes to seafood, there’s an added benefit.

“Europe and America are doing a better-than-average job at managing their oceans,” says Andy. “So if you live in Europe, and you buy European fish, you’re probably buying a fish that’s scientifically managed and reasonably abundant.”

Remarkably, 90% of the world’s catch comes from the coastal waters of just 30 countries. So it makes sense to buy from one that has responsible fishing policies. “The policies won’t always be perfect,” says Andy. “But the odds are that something caught off the British coastline is going to be a more ethical purchase than something caught off the coastline of, say, West Africa.”

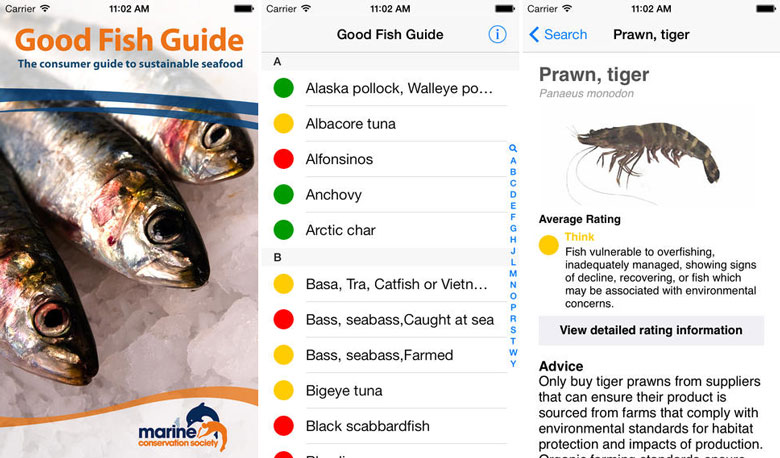

3. Pick a good guide. Just one

When it comes to researching the sustainability and seasonality of seafood, there’s a lot of advice out there – much of which is complex and even conflicting. Andy’s advice is not to strive for perfection. “Don’t obsess over the disagreements,” he says. “Pick one guide which is responsible and stick to it.” As an example, he recommends the Marine Conservation Society guide, which is also available as a neat app. Again, even if this, or any other guide, might not be right every time, it’s important to have a basis to work from.

Also quiz the people who sell you your seafood, rather than getting bogged down in written detail and debate, he says. “Ask them: ‘How do they know its honestly and sustainably fished? How do they know that farmed fish aren’t substituted for wild? How do they know that there’s scientific management happening in the places that they’re being sourced from?’”

– The key for Andy is simplicity. As we’re about to part ways, he quotes Michael Pollan, the journalist and activist, who famously summarised his approach to food in seven short words: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” Andy smiles. “I suppose if you really pressed us, we could come up with something similar. We might say: ‘Eat wild seafood. Not too much of the big fish. Mostly local’.” Simple.