Teeming and steaming

From medieval delicacies to jellied eels and pie and mash shops, writer, photographer and blogger Regula Ysewijn, aka Miss Foodwise, explores London’s love affair with eels.

Nor were eels solely a fish for the poor, as medieval cooking manuscripts show. But that changed in the 18th century, due possibly to a shift in tastes and probably also a fall in price: eel became very much a staple enjoyed by the working class. By the time Dr Badham was writing, eels were largely being sold on the street, along with just about every other kind of food.

A book from 1861 tells of 500 hot eel and pea sellers, with Old Street their epicenter. The hot eels varied in style, with one vendor serving them “as spicy as any in London”, and also in quality, with the writer insisting that even the poorest customers chose to buy from the best tradesmen rather than the cheapest.

London has a long association with eels. Now very much considered East End grub, they used to be eaten all over the capital. In 1853, the Rev Dr Charles David Badham, a writer, physician and entomologist, wrote that “London, from one end to the other, teems and steams with eels, alive and stewed; turn where you will; hot eels are everywhere smoking away.”

In the early Middle Ages, rents were even paid with eels and eel pies.

The elegant snake-like creatures were caught in eel-weirs made from wickerwork on the rivers Severn and Wye in Gloucestershire and in the East Anglian Fens. They were transported live to London in water barrels or by ships, to be sold in the two competing fish markets: Billingsgate and Queenhithe in Westminster, which was eclipsed over time and disappeared around the 15th century. Demand was so great that extra eels had to be imported from the Netherlands.

The traders bought their eels from Billingsgate, where watermen would row them out to eel boats moored on the Thames. These barges kept the eels in water and mud to be sold alive. Respected tradesmen used only live eels in their pies, but others mixed in dead eels, which was very much frowned on, even though the eels may have only been dead for a few hours. This helped feed the urban legend that piemen put all sorts in their wares, from dead eels to stray cats – or, in the case of Sweeney Todd, much worse.

Piemen sold meat pies, eel pies and sweet pies with fruit fillings depending on the season. They would walk the streets with portable charcoal ovens, crying out for trade and often visiting public houses to feed the hungry drinkers and gamblers. It used to be a very profitable business, but in 1861 the London piemen complained that they were losing trade to the increasingly popular “pie shops”, which sold larger pies for the same money.

One of the earliest and most celebrated was actually just outside of town, on Twickenham Ait, an island on the Thames to the west that became a popular destination for day-trippers from the bustling city. Some came by steamboat, others by rowing boat, but they all ate eel pies, and so Twickenham Ait became known as Eel Pie Island.

As pie shops spread across London, they started to serve mashed potatoes along with their pies, creating a meal instead of a portable snack. Many added eels to their menu too. It was the beginning of the end for the eel and eel pie street sellers.

By 1874, a contemporary trade directory listed 33 eel and pie shops in London. Some of those names went on to become pie and mash empires that still exist today, although with rather less shops than in their heyday.

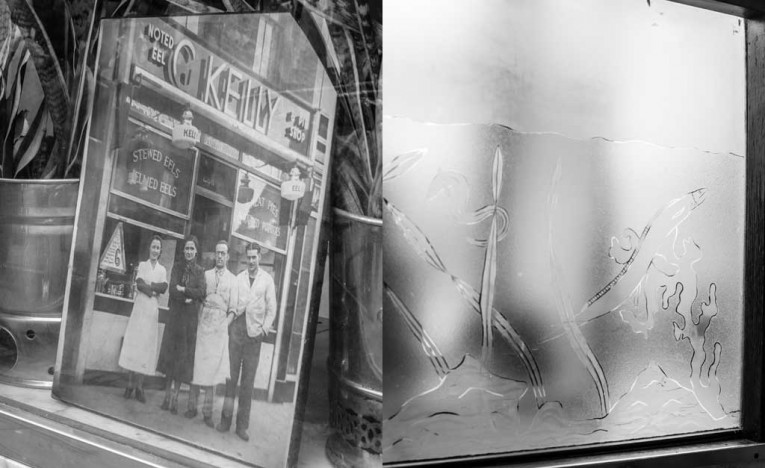

The Cooke’s eel and pie chain started out in 1862, a date enshrined in the mosaic floor of the original shop on Kingsland Road, now a Chinese restaurant: luckily its iconic interior has been preserved and listed. Pie and mash shops, as they were eventually named, all had similar interiors, many of which have been preserved: a mosaic floor and cut glass or mirror decorations depicting the beautiful swirling lines of the eels, and tables with marble tops and wooden benches lined along the white-tiled walls.

The kitchens had large ovens to bake the pies, a kettle for the hot eels and jellied eels, and water racks or drawers to preserve the live eels. The shops would often have a stall in front of their premises, selling live eels to people who wanted to stew them at home, and sometimes a window selling hot pies too.

Unable to compete with these flourishing shops, the street vendors had all vanished by the late 19th century. By 1920, Cooke had plenty of rivals, such as Michele Manze, who set up shop in 1902, and Robert Kelly, who started his empire in 1915. All still exist today and have more than one premises.

But they are not the force they once were. War and rationing hit pie and mash shops hard, removing both the working men that were their market and restricting supply of their product. Business picked up again in the postwar boom, only to drop sharply during the 1950s and 1960s as rising rents forced factories out of town, again removing their customers.

Many closed, but some survived and remain a big part of their local communities. Eel pie would never make the menu again, however, but hot eels and jellied eels remain to this day proper pie and mash fare, favoured not only by East Enders, but also by foodies and businessmen in suits and shiny shoes. Even David Beckham is a fan and apparently enjoys a side of jellied eels at his favourite eel, pie and mash shop.

If you’ve never tried jellied eels or hot eels, I heartily recommend you give them a try. Their flavour is fresh and delicate, only seasoned with a pinch of sea salt and black pepper and perhaps a drizzle of chilli or plain vinegar. And do go to one of the iconic pie and mash shops on your next visit to London and have a taste of times gone by. For a list of the best, click here.

Regula Ysewijn is a graphic designer turned food photographer and writer. She is currently busy writing her first book about British food, while photographing and writing for editorial and advertising clients. She also creates new visual identities for food businesses at the graphic design business she shares with her husband. And she is the editor of the acclaimed blog Miss Foodwise where she celebrates her passion for British food and culture. All the pictures on this page are by her.